On the 28th August 2017, I crossed from Germany into France — from the little town of Kehl into the city of Strasbourg where I will remain for the upcoming academic year as part of the Erasmus exchange program with BCB. As I had never visited France, I was more than excited for my Erasmus Exchange, and curious about the similarities and differences I would find between these two nation-states at the heart of the European Union. But, despite the attention I afforded the view from the bus window, I’m still not sure exactly when I crossed the border. There were no bells or whistles, no fanfare, no berets or baguettes in sight. The landscape remained unchanged and my fellow passengers continued to doze, or stare at their mobiles, uninterrupted. It was only when we disembarked that I noticed how road-signs and the displays in shop windows were no longer in German, but French. Listening in on the conversations of those who buzzed around the terminal, I quickly recognised its distinctive melody, a smooth and slippery river of sound falling unintelligibly upon my dumb ears.

Almost a month later and I can’t help but think the true wonder isn’t how similar these neighbouring countries seemed to me initially, but how language and culture are preserved despite their geographic proximity, and how deeply the notion of the border runs within the human psyche.

Maybe it’s got something to do with the overwhelming amount of bureaucracy one has to wade through in order to settle here. Far from being relaxing, my first weeks have been a frenzy to maintain my legality and officially register at the university. (To any second years considering going to France for their Study Abroad year — you have been warned). It’s almost like a rite of passage, and, once you’ve been initiated, you feel a certain fondness for and solidarity with the place you had to fight so hard to stay in. Yet there’s no denying the city’s charm. With its quaint architecture, bikeable infrastructure, and a surplus of student discounts, Strasbourg is a university student’s dream.

Having changed hands between France and Germany multiple times within the nineteenth century alone, Strasbourg represents a unique fusion of French and German culture and remains a symbol of reconciliation between the two countries post-WWII. It is the seat of several important European institutions, most notably the European Parliament, which has legislative function within the EU along with the Council of the European Union and the European Commission. I am lucky to be learning about Strasbourg’s history and place in the European Union in a class in European Economic Policy here. I won’t bore you with the complexity of the EU legal framework, which I’m only beginning to wrap my head around, but I think it is worth briefly outlining its history for the benefit of non-EU citizens or anyone who isn’t well-acquainted with its formation: The European Union was originally conceived of as the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and involved France, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg, and Holland. The coordination of these two industries was undertaken so as to promote peace and prosperity within Europe and to render a war between France and Germany “materially impossible” [*1].The EU as we know it today is the result of a gradual process of integration. In a nutshell, it can be thought of as an ongoing political project, an international organisation in which some policy decisions of its 28 Member States are transferred to the higher authority of so-called supranational institutions. It is (theoretically) based on the community principle, meaning that all Member States are ruled by a set of shared values and interests. However, this emotional basis of the EU has only begun to be stressed in recent years, and the translation of theoretical values to practical policy applications is one of the biggest challenges facing the EU today.

This was the topic of discussion in my first class on the subject last week. As I walked out of the school building, I struck up a conversation with an American girl who had seemed skeptical during the lecture.

“What did you think of that?” She asked me with a note of complaint in her voice, referring to the day’s lesson.

“I rather liked the teacher! She seems really knowledgeable about the subject.” I decided to keep my commentary positive.

“Oh, but, well, don’t you think it’s all kind of ridiculous? All the talk of shared values and whatever?” I was taken aback. “Maybe it’s because I’m American, but all this seems sort of wishy-washy to me. In the U.S. we’re all totally about competition, you know? How can anyone really buy into the EU?”

Her short commentary spoke volumes about the ideological divide between these two unions. I was stunned, unsure of how to reply. “Oh, okay,” I managed, and an awkward pause ensued.

“See you around!” she said, and we both took off.

I had never before truly questioned the values the EU claims to represent or whether its members actually uphold these values. Maybe I’m an idealist, but I think that we’d be lost without such guiding principles and that countries are clearly better off if they co-operate as a community than if they buy into a free-market ideology where every agent is pitted against the other. So I was shocked to learn in our next class that her opinion doesn’t represent as small a minority as I imagined: A third of the members of the European Parliament are openly skeptical of the EU. At what point did EU politics become so fractured?

The bonds of solidarity holding the EU together have been sorely tested in recent years with the “refugee crisis”, while the United Kingdom is already in the process of severing its ties. The rise of fascism and right-wing extremism across Europe has been a wake-up call as to the precariousness of our political reality. But, as the results of the most recent German elections have shown, this wake up call was not loud enough.

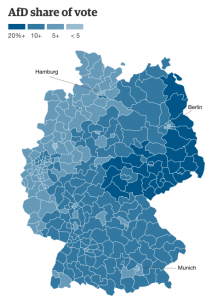

Though Angela Merkel was able to secure a fourth term as German Chancellor after Sunday’s election, the AfD — Germany’s equivalent of the UK Independence Party that advocates nationalism and anti-immigration — has entered the Bundestag as the third-largest party, securing 12.6% of votes and a projected 13.3% of seats [*2].

Living abroad most of my life, growing up in a world where skeletal children begged on street corners and bowed their heads beside car tires on the hot tarmac, where mothers rent out their babies to other beggars to generate greater sympathy, I got the impression that Europe didn’t have real problems. South African politics didn’t interest me as a teenager. It was something one avoided talking about in polite company. The state of affairs seemed too messy, everyone seemed corrupt, no one was making a positive impact. The news exhibited one scandal after the other and I learned to equate politics with senselessness.

Now I know better. Thanks in large part to my Liberal Arts education and the politics of my peers at BCB, I have come to realise that active engagement with politics is absolutely essential in maintaining the health of a democracy and that, yes, Europe does have its fair share of “real” problems. Though not as glaringly obvious as abject poverty and violent crime, these problems are manifest in political rhetoric. They dress in tailored suits and make slick speeches on a platform of anti-immigration, supposed traditional family values, and nationalism. Though I am a guest in the European Union, I believe it is everyone’s civic duty to engage with the politics of their surroundings in a constructive way. If we want to continue enjoying the time of relative peace and prosperity that has graced the EU in these past decades, we can not afford to take it for granted and must take the initiative to educate ourselves and, when we are able, to vote for those parties that nourish our democracy.

This is what we can do on an individual level. But this is not enough. To truly curb the populist sentiment rearing its ugly head in Germany, we must dismantle it on an institutional level. This is where education must step up to support “the cause of a democracy where citizens of the entire world are welcome, minorities are protected, and dissent respected. [*3]” Elena Gagovska artfully engages with this issue in her most recent article on “The Political Landscape Post Charlottesville”, asking where students and academics should stand on this issue and what the role of higher education is vis a vis politics. For the most part, I agree with what she argues — that education is inherently political. But there is one critical point on which we diverge; this is on the type of discourse that ought to be allowed in universities, at institutions like Bard or BCB, in contrast with what should be allowed in the wider political realm. Elena argues for the Principle of refusal as outlined in Geoffroy de Lagasnerie and Edouard Louis’ Manifesto for the Political and Intellectual Counteroffensive [*4] to extend to our university campuses:

Escape the imposed debates, refuse to recognize the validity of certain ideologues as counterparts and of certain problems as relevant. These themes make the confrontation of ideas impossible; their removal is the condition of the debate.

The reasoning behind this principle as Elena describes it is that, if we were to allow certain (intolerant and problematic) ideologies into the discourse, this would only push the discourse further and further to the right and would prevent us from dismantling systems of oppression and truly progressing as a society. By refusing to allow such ideologies a metaphorical place at the table, we also refuse them any shot at legitimacy. Furthermore, if we were to allow fascists into the discourse, they would make any further discourse impossible by endangering our democracy. This, I agree with. We must not put the core values of our democracy up for debate or begin to accept any shade of racism, homophobia etc as acceptable.

However, I would argue that we must make a distinction between the type of debate that should be allowed in the political sphere and that which might play out in a classroom or any other neutral platform where the consequences of conversation are not as far-reaching as those held in the Bundestag. The Manifesto’s interpretation of the consequences of allowing these opinions into the discourse is limited; it does not embrace our human capacity for critical thinking, nor does it consider the power of debate and conversation to deconstruct and reconstruct an individual’s innermost beliefs.

I propose that education, especially higher education, can best fulfill its function when it engages individuals in a Socratic dialogue. This tackles ignorance at its roots and prevents it from branching into the political sphere in the first place. Any student who attends BCB knows the value of the Socratic method first-hand. Helpfully defined by Wikipedia as “a form of cooperative argumentative dialogue between individuals, based on asking and answering questions to stimulate critical thinking and to draw out ideas and underlying presumptions,[*5]” the Socratic method works from the inside out. It also allows the interlocutors to understand why one person holds the opinions they do in the first place and to best address their misgivings in a way that is in line with democratic values. Instead of turning to populism representation, potentially problematic opinions should be allowed space on the stage of education where they can find answer and guidance towards the furthering of the common good. Furthermore, this sort of dialogue should be facilitated among people of all ages, in all strata of society. A liberal education should not be reserved for the privileged few and people’s politics, their social conscience, should not be left to the whims of circumstance.

The reality is that, though not considered “legitimate” by the majority of the demos, problematic and undemocratic opinions exist. At the end of the day, the voting process is anonymous, and one ballot counts the same as the next. As the recent election results evidence, rage and refusal are not helping solve the problem of populism. With this assertion I am not attacking the historical value of protests in achieving real political change and as a means of expression. Their value is self-evident. However, we must go further than this by stepping back from our slogans and shouting, laying down our weapons of rhetoric, and engaging with the opposite side intellectually before they manifest themselves in parliament. To quote Einstein, “We cannot solve our problems on the same level of thinking we were at when we created them”. Populism is a phenomenon that has its roots in ignorance, and ignoring this ignorance is a grave mistake. Populism “conceives the people as One — namely, as a single entity consisting of leader, followers, and nation. This trinity of popular sovereignty is rooted in fascism but is confirmed by votes,” twisting fact into fiction and endorsing stupidity[*6].

The gates of change are only opened from within; the key to these gates is an education that realises and embraces this function. As Elena rightfully demands of us, we, students and academics, should be at the forefront of the promotion of values of respect and human dignity. But perhaps we can best fulfill this function not by refusing the other side a voice, but by engaging with them in such a way that brings their error to light.

Notes:

- Schuman Declaration. 9 May 1950.

- German Elections 2017: Full Results. The Guardian. 25 September 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2017/sep/24/german-elections-2017-latest-results-live-merkel-bundestag-afd

- Botsein, Leon. American Universities Must Take a Stand. The New York Times. 8 February 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/08/opinion/american-universities-must-take-a-stand.html?mcubz=3

- Manifesto for the Political and Intellectual Counteroffensive. Los Angeles Review of Books. (Originally published in French in Le Monde).

- Socratic Method.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Socratic_methodFinchelstein, Federico. From Fascism to Populism in History. 26 September 2017. http://www.publicseminar.org/2017/09/from-fascism-to-populism-in-history/#.Wcu4ktMjG9Z