This story is part of Fiction Month 2020. Click here to view the stories featured this Fiction Month, as well as past fiction pieces.

I

A man stands in a train station. He wears a wide-brimmed hat and a long black coat; his hair—what little peeks out from beneath his hat; one suspects he is thinning—is dark, streaked with gray, and unkempt. It runs down the back of his neck, and even out over the collar of his shirt. His face is lined with age, but there is little hair on his cheeks: his grooming is impeccable. He stands within the sight of a great standing clock, but he does not look at it. Indeed, he seems almost to be quite pointedly looking away from it: as if he fears what may happen if he looks at it too closely. He trembles. I can see it now. He is shaking with fear. Sweat runs down the back of his neck. Within his pockets, his hands are clenched into anxious fists; his palms are slick wet.

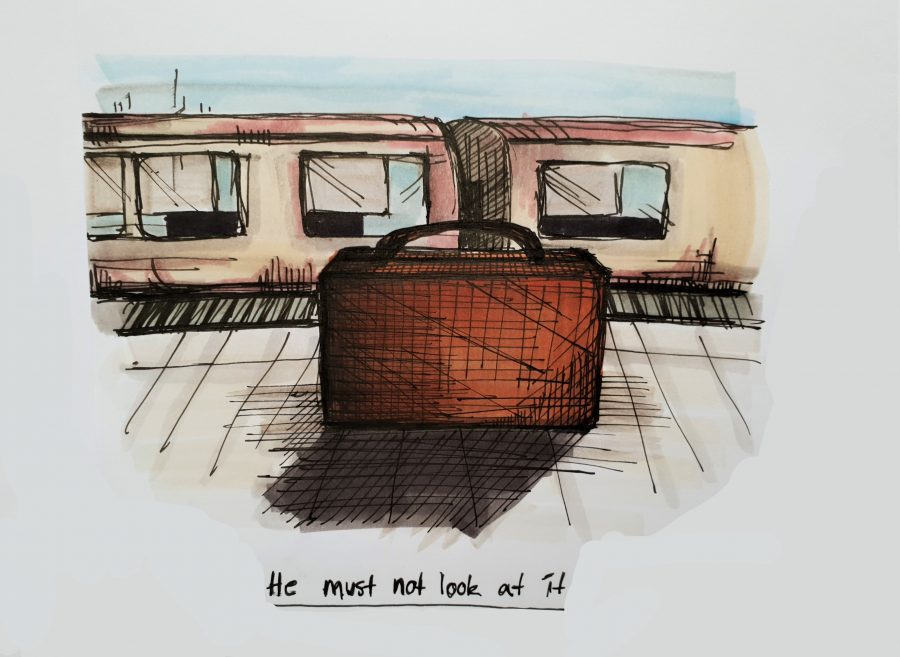

There is a briefcase resting at his feet. From time to time, his gaze flits down to it, and lingers for a single moment. His pupils shake, his lips quiver, and he looks away. In his mind, he promises himself that he will not look at it for at least another thirty minutes. He must not look at it. But he quickly breaks this promise. He blinks more often than is, perhaps, normal: as if he is in shock, or on the verge of tears. At least once, he opens his lips, and his tongue runs over the cracked skin. His saliva tastes warm and sour, as it does when one has just woken up. Perhaps he has been asleep; perhaps he still is. He sniffs the air, and flinches: there is something there that he did not expect. His head draws back, his back straightens. It is the most he has moved. Is he waiting for something, or is something waiting for him?

His ears are large, and stick out noticeably from the sides of his head. He can hear almost perfectly all the myriad sounds that infest this place. A soft whistling sound: the wind. It chills him, makes the hairs on the back of his head stand up. The electric lights above, flickering and stuttering, as their wires whine. All sound in the station, save for the wind, is mechanical: the creaking of train cars miles away, riding on rails to places unknown; the sound of pistons and levers, surging for some unknown purpose; the hum of electricity that surrounds and stuns and silences all. A few months earlier, flies, dazed and blinded by the lights, might have buzzed about overhead; now, with winter’s coming, they are all dead, or lying in wait for spring. The ground is cold and dead and silent; the Earth is giving up. And outside, the last rays of the setting sun are vanishing into the night. Darkness will soon be all around. He fears this most of all, because he does not trust the electric lights to stay on. Murmuring under his breath, he prays for his deliverance.

To whom, exactly, does he pray?

When the night has closed in at last, and shadows lie all about him, he closes his eyes. He whispers something under his breath, but his lips barely move. They resemble nothing more than a thin line across his face, a gash in his callow flesh. Some emotion passes over his face, clouding his features, stiffening his spine: anger, born of fear? Is he enraged by his impotence, his terror? Does he wish he were stronger? He takes a deep breath. In, out. His eyes open, and his gaze flits over the scene. Shadows seem to take on lives of their own, and in his mind there can be no life that is not antithetical to his, and so these shades must be the soldiers of an infernal army, come to surround him and bring an end to him. He does not look away, but stares ahead, gaze fixed, head shaking, as he desperately tries to ignore them. Seconds pass like hours. His chest heaves steadily, but deeply, such that one can see it even when his body is wrapped within his clothes—the one-time cocoon that now can offer him nothing at all. Without warning, a shadow looms from behind him. He turns. He blinks. Then he runs.

His first steps are awkward; he trips over his briefcase, knocking it over, and he stumbles, arms whirling in the air a moment, and he looks back, face contorted with terror and pale as death, but he manages to get his footing again and runs on, footsteps echoing like cannon fire, like church bells. His hat flies off his head and is caught in a sudden draft, takes on the form of a spectral crow, flies into the rafters and disappears, and he runs on, scared out of his mind, and first garbled speech first comes from his mouth and then turns to indistinct shrieks of terror. There is something cruel in the air, something poisonous, like the malodor of the tomb, and he knows it; perhaps that is what he flees from, more than anything else, although even he is not sure, it seems to him as real and present and terrible as anything, and so he runs, beyond even the walls of the station itself, until he is in the darkness, until he is part of it: another shadow, another phantom. Still he runs.

He runs into the night, on and on, and does not stop until I wake.

II

For the past few years I’ve been having a strange dream. It doesn’t come every night, and with each iteration the details change in very slight proportion: it is a stage play, not a film, and from time to time, a lighting rig may break or an actor may forget his lines. Underneath, the script—the substance—remains the same. It is one dream, hanging over me, tormenting me, long after I have awoken.

It begins in my grandmother’s house. I recognize it immediately, because I know it well, having visited many times as a child. I know its stucco molding, its lace-and-ivy wallpaper, the lingering citrus scent that permeates every room. Also familiar to me are the statues that rest on every surface in the house. Small porcelain angels, white and tranquil, stand next to wooden children with overlarge heads, androgynous bodies in painted-on sailor suits: these I remember, these silent observers, witnesses to my memory. All dreams, I suppose, draw upon what we know, what we have seen in our waking lives.

In my dream I am among them. I sit in the living room on a sofa with a white blanket thrown over its cushions. I do not know how I came to be there, but I have a sense of anticipation, or, perhaps, anxiety. I’m waiting for something, and I fear it, so much that I can’t turn my head, not a single inch, to look at the doorway, and so I stare straight ahead, at the fireplace opposite me that has never housed a real fire, and at the figures that rest on the mantle, and they gaze back. I feel their gaze on me from all corners of the room, a silent garrison. It can only be my fear of them which keeps me trapped in my seat.

The light grows dim, which startles me, as I had thought I was sitting in the light of day; but now there is only darkness outside, and within, a hideous red light that casts all the ornaments of the room in Satanic crimson. The cherubic smiles of the dolls turn to twisted visages of cruelty and malice, and the placid angels are callous, malignant demons. They may not be the perpetrators of my demise, but they will joyfully bear witness to it. Everything is red, even the ground beneath my feet. Blood has been spilled here before, I realize, and soon it will be again. Like the altar of the Trojans: here is where the blameless are slaughtered, innocence demolished, the holy made profane, all the wretched evils of this world terribly revealed. In this darkness, evil is real, and it is present.

A blur—black on black—arrives at the edge of my vision, and I know, in one shattering instant, that I am no longer alone in this Hell; but this newcomer is no Virgil. For a moment, I am still, my heart threatening to burst out of my chest, as I hear and see and feel it move towards me, and in anguished silence at last I turn my head and look—and in that instant, I finally understand, I finally know. Precisely what, I never remember in the light of day, but whenever I wake up I am screaming.

Brief flashes come to me after I have tossed aside the sheets, climbed out of bed, washed and dressed myself, and gone out to face the world. They come unbidden, like some imp whispering terrible things in my ear. I may be on the bus, in a café, sorting papers, and they come, freezing me where I stand: black-and-red tableaus; screaming, contorted faces; the smell of blood; and a curious sensation, running across every nerve and pore in my body, as if I am being crushed into nothingness, from my legs to the crown of my skull.

III

It is 1:02 AM, so says the glowing red light, and it has been 1:02 AM for several hours, if such a descriptor can have any meaning in this context—does time lose its meaning if it ceases to move forward, just as a film that stops mid-reel is no longer a “movie” (short for “moving image”, of course)? I tease over the idea in my mind. I am wrapped in several layers of bedsheets, but still I lie awake, unable to bring myself to sleep, or even to conceive of the notion of sleeping. I woke at 1:02 AM. Considering my current predicament, my awakening and the seeming halting of time itself might not be linked—it might have already been 1:02 AM for days by the time I awoke. There is simply no way of knowing. I am on my side, my head rests on one hand, my legs are tangled below me; my hair is a mess, a veritable haven for birds. I’d like to get up, go to the bathroom, and take a nice, long, steaming hot shower—and why shouldn’t it be as long as I like? I’m in no danger of being late for anything. Laziness, then, keeps me here; a refusal to abandon, even momentarily, the tender embrace of my bedclothes, as I lie here, unbearably awake in the face of the end of reality as I have known it up to this point.

Might civilization continue in some form? Even if the Sun refuses to rise, if there are others, like me, who are capable of rising and going about their business in spite of the arrest of any sensible entropic progression, it is certainly possible that we might continue our lives much as we always had. We would have to make some adjustments, of course, including some rather fundamental ones, since schedules can no longer be based on any clock besides the biological, and speaking of “working hours” or “time to lose” would be nonsensical in our new context. Yes, whatever society emerges in this brave new world of 1:02 AM, this bizarro Shangri-La, will be far removed from life as it had been in the before times (before, time?), but it will be life nonetheless. I remain unconvinced that such a thing will occur. I admit that there may be others like me, awake at this minute, but so long as I remain in my bed I have no means of knowing for sure, and in any case I don’t like the idea very much. It seems far more likely that this is my own personal nightmare, which I must suffer by myself. Yes, this is my fate, justly earned; no doubt I said earlier in passing how I wished I could have a more extra hours of sleep each night, and—how the tale twists! Now I have as long as I want to sleep, but my wish has been ironically subverted, like in some half-baked episode of The Twilight Zone. Any minute now, Rod Serling will step into the frame and go off on some spiel about how richly I deserve this, and he’ll make some cute witticism and the lights will fade and I’ll just be left here in the dark to wait eternally for 1:03. Very clever, Mr. Serling. Unless, of course, this extended minute is just a dream by itself, a phantasm born of my own mind, fated to vanish when some outside stimulus intrudes into my reverie and drags me back to waking life, and within minutes of my rousing all of this unpleasantness shall be forgotten, and I will return to the life I have always known.

That might be the greatest fantasy of all: to awaken and find that one’s living hell was only a bad dream; that the abyss into which one had fallen during a moment of distraction earlier in life, unwittingly and undeservingly, was as escapable as a cage made of clouds; to escape from all of life’s miseries with only five words: “It was all a dream.” No, it isn’t true. Or it is, but everywhere, and at all times: supposing the dream extends infinitely into the future and the past, encompassing all of history and memory, and that there was never anything before the dream and there will be nothing to come after it. No, no, that cannot be, that is too much to bear, too much to imagine. The only acceptable possibility is that my predicament—too weak a word, perhaps; something more Homeric might suffice, but I cannot find it right now—is real, all-too-real.

I think I have just made a breakthrough.

George Menz is an exchange student from Columbia University, majoring in philosophy.

Hi George, I really liked your story, particularly your liberal useage of punctuation and allegory.