I only went to see two films at the Berlinale International film festival, and I only stayed awake for one and a half of them. Despite the negative review my nap seems to suggest, the effort with which I attempted to keep my eyes open tells a different story. Both films, Centaur and Railway Sleepers, were wonderful — beautifully shot with subtle but imaginative narratives. The festival lived up to my expectations twofold, and my expectations were far from low.

Founded in West Berlin in 1951, the Berlinale was originally conceived by an American film officer of the US Army as a propaganda tool during the Cold War. It was meant to be a showcase of the so-called “free world.” Hitchcock’s Rebecca was the very first film to be shown, and, for the first years, the festival was dominated by American and British works. It wasn’t until 1955 that a German film won the top prize. Originally, East Berliners were also able to see films for lower prices at specific screenings. These screenings ended in 1961, but the propaganda continued as the wall went up, with 500 movie posters hung to be visible to East Berliners. The festival grew from there, eventually shedding the US influence. Now it is one of the most highly attended and well-reputed international film festivals in the world, as well as one of the most influential. After two films watched and 10 euros spent, I understand why.

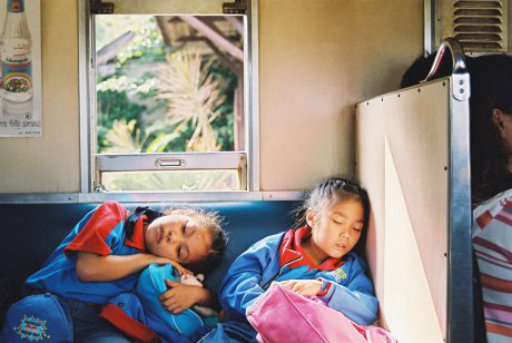

The first film I saw and unfortunately napped through was ironically titled Railway Sleepers. Director Sompot Chidgasornpongse spent eight years filming people on sleeper trains in Thailand. Backed by the constant noise of the wheels grinding along the tracks, the whole 102 minute film is a carefully sewn patchwork of film clips of passengers — both awake and asleep. There is very little speech to be heard above the train sounds, but we are still able to witness brief glimpses of the stories of the lives of these suddenly intimate strangers. There is the little boy who loses his tooth, drunk tourists dancing, and an old man praying silently. The film allows us to fully experience the sleeper train in over an hour of people-watching and illustrates the director’s apparent obsession with documenting the melange of feeling in life. A particularly strong moment in the film that will stay with me was of a young girl intently watching the shadows her fingers made on the seat next to her as she moved them back and forth in the sunlight. At some point she seemed to gain awareness of the people around her or the camera capturing her, and, drawing back her hand, looked around self-consciously. After only a brief pause, however, she was pulled back to the simple magic of the changing shadows she could create. As well as being an immersive, experiential film, Railway Sleepers demonstrates a great love for the beauty in the mundanity of human experience.

Centaur also seemed to find magic in the everyday. Centaur both stars and is directed by Aktan Arym Kubat. The film’s protagonist lives a quiet, simple life in Kyrgyzstan with his wife and son. Nicknamed Centaur because of his obsession with an old myth, the man steals the fastest race horses and rides them — sans saddle and with arms lifted — for a night, then lets them loose to return to their owners the next day. Caught up in messy situations within the community, he seems to be in search of a connection to the past, a time before man’s destruction of the natural world. Riding the horses, which he calls “the wings of man,” seems to partially satisfy his need for a tether to the enchantment of the old days while allowing him to find beauty in the present.

One night a few months ago, while waiting for the U-bahn on my way home, I witnessed a similar sort of magic. There was a man sitting on the ground, busking. He was old and having trouble sticking with one song, frequently interrupting himself to converse with passersby. A couple of loud, drunk men walked up, dropped some coins into the cup, and requested a song. As the performer began to play, a plump, red-haired man was jokingly called on to dance. Though the suggestion was evidently meant in jest, he surprised us all by launching into a skillful Irish jig. The crowd formed a messy circle around musician and dancer, clapping along until the train came and we all dispersed. I remember thinking to myself how easy it is to fall in love with strangers, how I wanted to wrap my arms around that moment and hold it, preserve it, never forget it.

That night, I was reminded of a poster given to me by a friend that reads “To see beauty is simply to learn the private language of meaning which is another’s life–to recognize and relish what is.” Both Centaur and Railway Sleepers attempt to do just that. They are stories told with the same amazement and fascination that manifests most acutely in childhood. Watching them, I felt like a kid looking from the backseat into other people’s cars on the highway, wondering about the lives inside, or that same sense of perfection I experience when, just before sunset, everything glows pink and gold. These are feelings that invariably slip from our grasp, but, in the silent darkness of the theater, these films make space to stop and watch. Perhaps more importantly, they suggest that, when viewed from the right angle, something as banal as a man snoring on a train can become wonderfully cinematic.

I really loved reading your “blog” Anna. Am so glad your mom forwarded it to me. So great that you have the opportunity to appreciate simple moments that so many of us don’t take time to see.

Nice writing, Anna. Well done!

Great writing Anna! And fun experiences.

Where did you learn to write like that? Reading your blog makes me want to see those movies. And learn from your teachers.